A beaver dam rolls to its doom. A man bustles cartoonishly from the path of the cascading river water. Skip back in time: to before the demise of the beaver’s home. Before the river washed away the unsung flora and fauna flourishing under the dam’s protection. Before human success. In water-proof overalls and high wellington boots, the man removes sticks and mud via accelerated footage. “Guys… What’s up? I’m standing in front of a big beaver dam. The heavy rain this week caused the water level to rise and the water can’t drain so flooding can happen easily. I have to break this beaver dam. Even though I love animals very much.”1

When I was a boy I wanted to conquer the tree in our back garden. It stood gnarly, casting tarantula shadows on our house in the stretched-out daylight of the summertime. I’d perch at its base at the ripe young age of seven, strategising how to take it down a peg or two. When I finally tried to scale its wood I found a feeling, in a place beneath words, less violent than conquest.

The tree’s chunky base forks into two trunks close to the ground, which in turn fork into two more trunks higher up. From there, forks beget forks until logs become branches become twigs. In my first shaky climb, I yearned only to reach the second fork towering above my soft, silly head; so high that it may as well have caressed the stars. Two months of summer adjusting my body to collaborate with tree’s stern physique, clattering upwards regardless of how hard my heart was sending blood rushing to my mind as fear fuel. Still, figuring out the choreography that took me higher brought a strange calm. When I got to the second fork, I saw the unkempt back-gardens of my neighbours and people streets over looking like ants. In one climb, I was bigger than everyone. Isn’t it funny how the world changes shape when you shift perspectives? In climbing the tree, I got close enough to realise its bark was a mirror and in the dull sheen of the rhytidome wood, courage stared back.

A shirtless man erects a cairn bridge supported only by its own tension by a forest spring. He tries to balance bigger rocks on the shaky structure—as if he believes himself exempt from the inevitability of gravity. He is not. The cairn bridge takes an Icarian tumble. Accelerated footage: Him piecing together a cairn bridge, his micro-movements and rocks jostling build a steady foundation, balancing rocks of comically varied sizes with careful precision. Finally, he steps back to reveal an impressive monument to his own hubris.2

In my adolescent years, my mother and I fought like dogs, cats and cartoon mice. I was unable to articulate the pressure of contorting to nonsensical, social etiquettes, the patriarchal compression of growing from boy to man, osmosis transfers of racism, my cousin who was close to my age that passed away suddenly of malaria that no-one ever talked to me about it, an educational system that penalised creativity and flattened intelligence into a memory test, the undiagnosed neurodivergence exacerbated by the bath of hormones boiling in my body and the general alienness of teenhood. Instead of words, my language of choice was stealing money and finding poetic ways to talk about stabbing people over grime tempo. With the daggers-in-hand, I’ll show you who’s magic like Alakazam. My mother, similarly unable to articulate the pressures of her own internal world, slapped me clean round the face in the middle of April for a reason neither of us can remember. I was bigger than her physically but cognitively, my brain still needed a fair few years in the air-fryer. Her smack opened a tree-like fork to who I could be. I wonder if she read my mind—as mothers seem supernaturally prone to do in choice instances; like when you misplace your wallet/keys and they know which exact jacket pocket to look in. I wonder if she could tell that I was considering striking her back. I stormed past her instead, seeking refuge in the tree. I sat in the second fork for hours. It had rained heavily that day and at one point, I wondered what it’d be like to slip and land crunchily on my neck. How peaceful it’d be—to dissolve into the dew-licked grass. Whenever it rains in April I think of Bambi. My dad returned home just as the sky put on its prettiest colours for the sunset and the tree let me carve a heart into its wood with a kitchen knife. Between scrapes, my parent’s argument about sending me to Nigeria bled through the glass of the patio doors.

Two faceless men strangle a rock with what looks like an oversized bike chain. With every crank of this metal contraption’s lever, the chain tightens. A voice coos, “Roxy’s in the background watching”. Roxy—the dog—is not watching. The men crank harder. The metal creaks. The rock bursts. Rewind: The rock bursts again in slow-motion. Water spills like guts. The weary sigh of Gaia wafts into the air, as if a gentle spirit—millennia old—whose rest was meant to be eternal has been disrupted, forced to breathe amongst the living once more.3

When I brought the woman I thought I’d marry to my family home, she asked about the tree in the back garden. I didn’t know what to say. It exists as thoughtlessly as breathing. I told her I fell out of it once. Three years later, I suspect we will never speak to each other again. I don’t know why I lied about falling.

A man scoops away beach sand with a shovel as water from a nearby river flows into the cavity. Accelerated footage: gruelling labour with sped-up grunts and the chuckle of nearby friends. Finally, sea and river merge in a small stream. Chop forward in time: the freshwater of the river rushes to the saltwater of the sea. Chop forward: the waters pour together in a maelstrom forming a large creek; walls of sand slowly crumbling from stress. The shoveller of the estuary whoops and hollers. “This one’s gonna be gnarly!” He grabs his board and surfs in the vortex of his freshly carved, personal creek.4

It used to be my job to rake the leaves. It was the chore I hated most as a teenager, especially when the dry leg of autumn—summer’s chaser—came to a close and all that was left was pre-winter; with its moist, clingy leaves and early darkness. I’d pile the leaves and pick them up with two claw plates, one in each hand, and drop them into the organic recycling bin. Everything about it was tedious. The claws never picked up enough leaves. The rain perpetually drooled. The cold was always uncomfortable, and on the blustery days, the whole ritual felt Sisyphean. Cleaning inside the house was much less offensive to the senses. Washing dishes is downright therapeutic.

Last autumn, my father knocked on my bedroom door.

‘We’re cutting down the tree.’

My heart broke along a cardiac fault line I never knew was there. Upholding the British rule of decorum, I asked through welling tears, oh, why? He said our neighbour, an 80-something-year-old white woman who lost her husband a couple years back, said the tree was obstructing the sunlight to their house. “So she wants kill our tree over sunshine she can get by stepping outside,” congealed in my mind, glopping out of my mouth as: Oh. Right.

After moving back home last year, I found myself awakening to the soundtrack of my father raking leaves. A pang of guilt scratched with every comb.

I should probably be doing that.

The blueness of tragedy is that we understand them. I wanted to plead with my father’s choice to cut down the tree but I hadn’t tended to it for years. He rose to take care of it because he had to. When I eventually move out again, he would have to rake the leaves—year in, year out—in the damp British gloom as he grew older and less mobile. I relinquished any sway I had over the trees fate the moment I left the leaves unraked. For the umpteenth time in my life, I felt my neglect had lead to death.

Yet, something about my neighbour pressuring my dad to cut down the tree churned the acid of my stomach. To feel so entitled to destroy a thing she had no claim over—the sanitised bloodthirstiness—it freaks me out to know I’m living so close to someone so indifferent about bringing death to a stationary life. Perhaps it freaks me out more that the world encourages and bends to their whims.

When the surgeons came to take down the tree, I went for a long walk. I returned and the tree was gone. This majestic being that drunk sunlight before any of us were even born—cut down because an elderly, white woman wanted to spend her last years on this earth basking in the sun. What cloying irony.

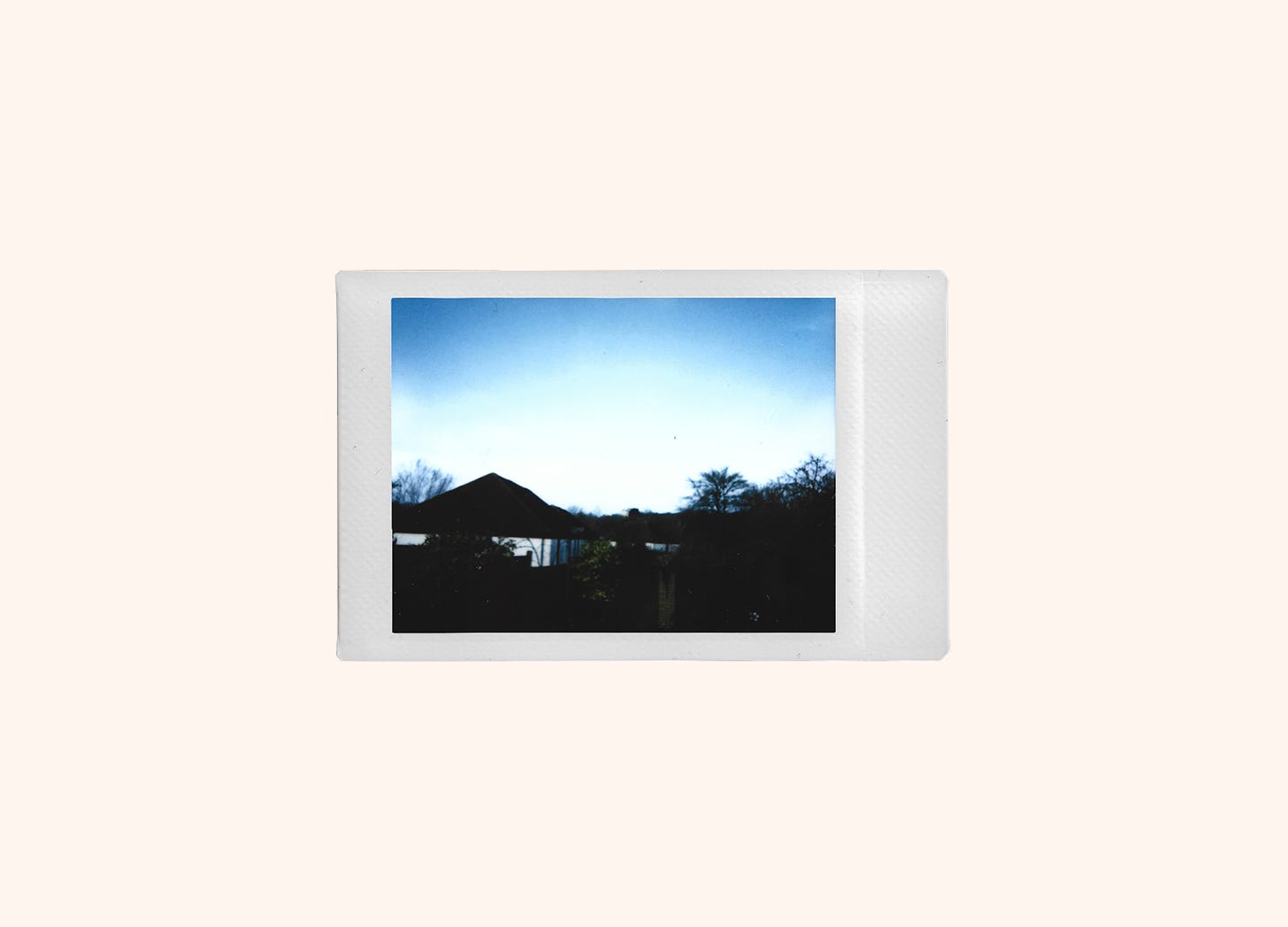

Days later, I went out to the stump. The Autumn rain left a sheen on the dead new surface, an alien smoothness. I looked up and saw patches of the sky I’d never seen before. The world changed shape again. With my palm on the gaping wood wound that will never heal, I whispered I’m sorry. At the time, I was being haunted by the words of an argument I should’ve never instigated. “You lack accountability”.

My tree deserved better than nebulous sorrow.

I’m sorry I didn’t save you. I didn’t even try. I confronted no-one who wanted to end you. I did little to care for you. I gave up nothing to keep you. I wasn’t as brave as you showed me how to be. You gave me so much and I let you down. You may not have been chopped down by my hand but you fell from my lack of action. All I can say now is that I will change from this. I’ll learn from you—to stand tall in my own skin through rain, shine and snow.

A beaver drags a toy duck across laminated flooring and drops it in a doorway. Like moths searching for the moon who careen to their deaths in the incandescence of a bug-zapper, the ancestral hardware of the beaver’s need to build a dam is wired as deep as the spirit itself. In its wood-carving buckteeth, the beaver drags a Christmas tree, a Spongebob Squarepants plushie, a towel, wrapping paper, a slipper to clog the doorway and make a reservoir of the room. Every slow move is drenched in melancholy. The camera keeps rolling like prank footage. Who made the beaver an orphan? Why and what’s the reason for?5

My mother is the only person who shares how I feel. We mourn the tree together, purging our indelicate feelings in the confines of car rides and restaurant dinners. Then we return home and look out at the back garden and see the unobstructed sky as a tragic void all over again. I don’t know what to do with all the clarity. I am piss and fury all along the chain—at my neighbour’s violence, my father’s acquiescence, my own bitten tongue. There is no fireplace for my anger and no chimney for its resultant woe to billow out. I no longer exchange pleasantries with my neighbour, a juvenile protest. I’d rather vent into the void of the internet before I share my feelings with my own father. I bust a joke with my inner child, at least we finally conkered it! before realising it isn’t gallows humour but part of the execution. I recite the words, it was just a tree in an effort to stave off tears, as if calling a tree what it is in a dismissive tone is enough to quell how I feel about its ending. It was just a tree means nothing when you know all too well that things are other things.

Which means this essay is something other, too. An allegory for white supremacy’s gluttonous consumption of the natural world. A personal confession of guilt. A journal entry about grieving. A cautionary tale about the consequences of inaction. An obituary for one of my oldest friends.

This is so beautifully written. It reminds me of the neighborhood I lived in a few years ago, where I’d walk in the same circle every day. One day the sun was setting just the right way through a tree in a neighbor’s yard, and I wanted to take a picture but instead thought to myself “it’s fine. she’ll still be there tomorrow”. The next day they had cut it down and nothing really captured that private gut punch until your story here

Inigo you almost had me crying at 5am😭

I'm in awe with how you described this tree and your connection to it and what grief looks like for you.

Thank you for blessing us with your stories.♥️